Robert Adams: 15 Key Observations on Photographing the American West’s Transformation

Robert Adams’ photography stands as one of the most significant documentations of environmental change in the American West. After abandoning his career as an English professor in the mid-1960s, Adams embarked on a photographic journey that would span more than five decades, creating an unparalleled record of how suburban expansion and industrial development have transformed the Western landscape. His work, beginning in Colorado and extending to the Pacific Northwest, offers not just a critique of environmental degradation but a nuanced meditation on what remains beautiful in a compromised world. Below are key some observations I have made from viewing his work, examining the themes, techniques, and insights that have made his photography both influential and enduring.

1. The Art of Documentation Without Judgment

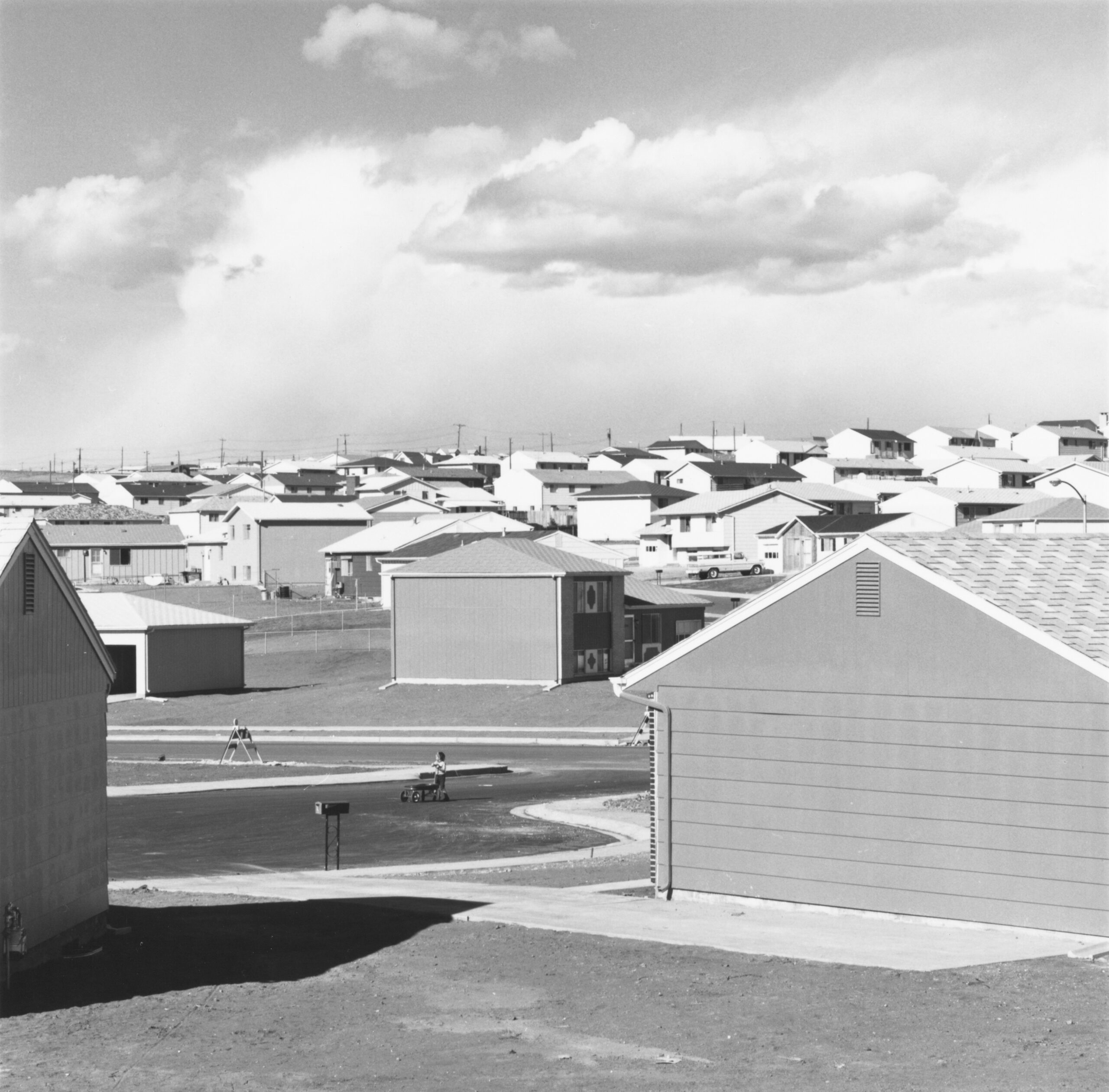

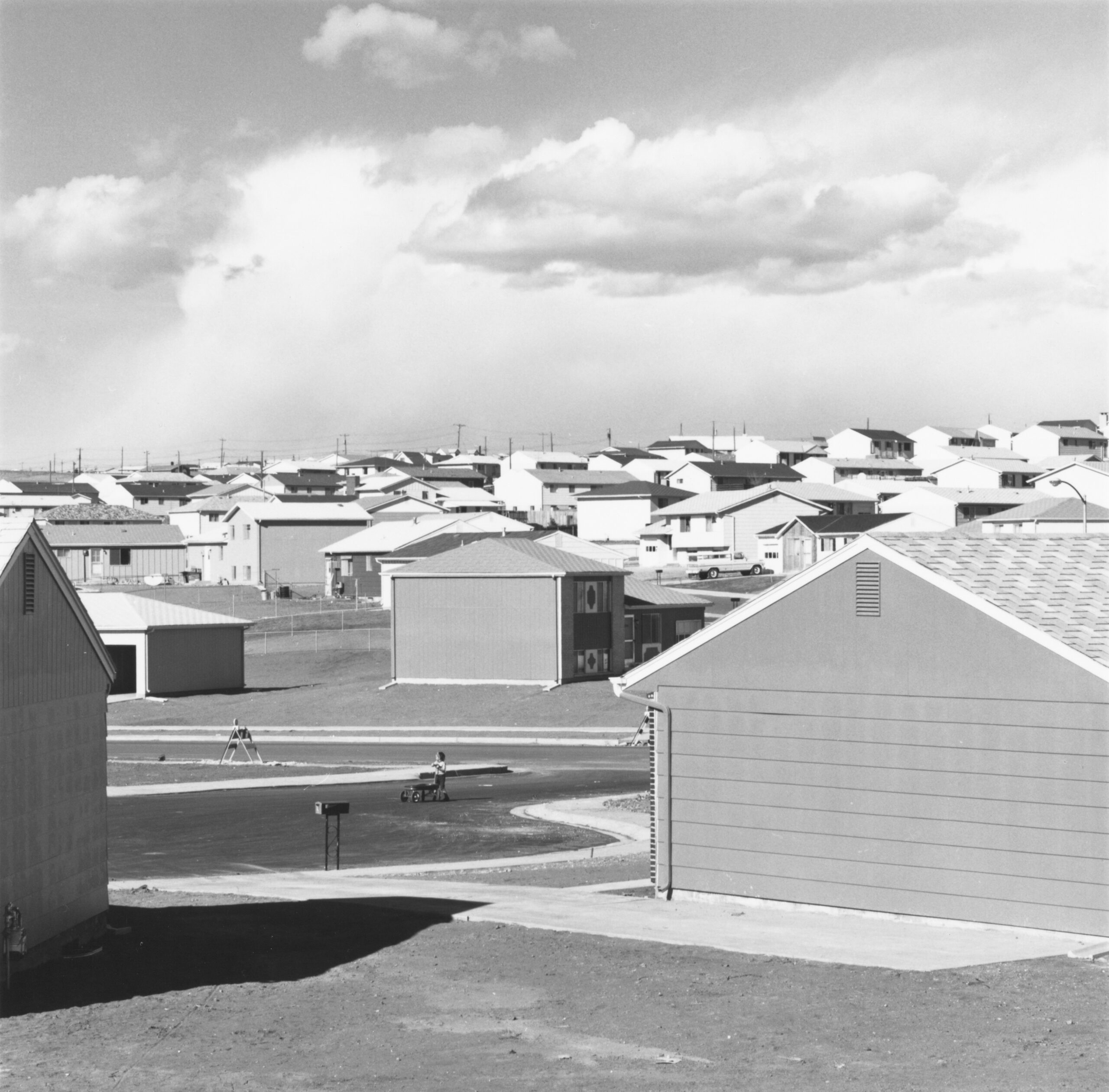

Adams’ approach to photographing suburban development marks a significant departure from traditional environmental photography. Unlike his predecessors who focused on pristine wilderness, Adams confronted the reality of human intervention head-on. In “The New West” (1974), his groundbreaking study of Colorado’s Front Range, Adams photographed tract homes, mobile home parks, and strip malls with the same careful attention previously reserved for untouched landscapes.

Consider his photograph of a Denver suburb against the backdrop of the Rocky Mountains. The image shows rows of identical houses stretching toward the mountains, but Adams’ composition neither condemns nor celebrates this development. Instead, through careful framing and attention to light, he presents the scene with a complexity that invites deeper consideration. The mountains remain magnificent, even as human development encroaches upon their foothills, creating a visual tension that speaks to larger questions about progress and preservation.

His participation in the influential 1975 exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” cemented this approach, helping establish a new way of looking at landscape photography that acknowledged human presence without resorting to either celebration or condemnation.

Takeaway: When documenting controversial subjects, strive for a balanced perspective that acknowledges complexity. Allow the viewer to engage with difficult questions rather than presenting them with predetermined conclusions.

2. Finding Beauty in the Compromised Landscape

Unlike many environmental photographers who seek out pristine wilderness, Adams deliberately focuses on landscapes that have been altered by human activity. His work in “Los Angeles Spring” (1986) demonstrates this approach perfectly. In these photographs, Adams finds moments of surprising beauty in the heavily developed Los Angeles Basin.

One striking example shows a single tree surviving in a newly developed area, its branches silhouetted against a smoggy sky. The image could easily become a simple criticism of urban sprawl, but Adams’ careful attention to light and composition transforms it into something more complex. The tree becomes both a survivor and a symbol of nature’s resilience, while the quality of light filtering through the smog creates an unexpected ethereal beauty.

This ability to find beauty in compromised landscapes stems from Adams’ philosophical belief that we must learn to see beauty in the world we have created, not just in the wilderness we’ve lost.

Takeaway: Learn to find and reveal beauty in unlikely places. The photographer’s role isn’t just to document pristine nature but to help viewers see beauty in the world as it exists.

3. The Power of Light in Environmental Documentation

Adams’ mastery of natural light transforms ordinary scenes into profound meditations on place and time. His “Summer Nights” series (1976-1982) represents perhaps his most sophisticated exploration of light. These photographs, taken in Colorado during evening walks, capture the brief period when artificial illumination begins to compete with natural light.

Consider his photograph of a suburban street at twilight. The image shows a line of houses with their windows glowing against the darkening sky. The artificial light from the homes creates pools of warmth in the gathering darkness, while the last remnants of daylight provide subtle detail in the shadows. This interplay between natural and artificial light becomes a metaphor for the larger relationship between human development and the natural world.

Takeaway: Study how different qualities of light can transform a scene. Understanding the emotional and symbolic potential of light is crucial for creating images that transcend mere documentation.

4. Simplicity in Composition as Ethical Choice

Adams’ straightforward compositional style isn’t merely an aesthetic choice but an ethical one. Having studied the work of 19th-century survey photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan and William Henry Jackson, Adams adopted their direct approach but applied it to contemporary subjects. His compositions often employ straight-on views and careful attention to geometric relationships, avoiding dramatic angles or artistic flourishes that might distract from the subject matter.

This is particularly evident in his book “What We Bought” (1970-74), where his photographs of Denver’s rapid suburban expansion employ deliberately simple compositions. One notable image shows a new housing development under construction. The frame is divided horizontally by the horizon line, with the skeletal structures of unfinished homes in the foreground and the vast Colorado sky above. The straightforward composition allows viewers to focus on the reality of transformation taking place.

Adams has written extensively about this approach, arguing that dramatic compositional devices can become a form of manipulation that distances viewers from the reality of what they’re seeing. His simple, direct style becomes a form of visual ethics, an attempt to show things as they are rather than as how we might wish them to be.

Takeaway: Consider how compositional choices reflect ethical choices in documentary work. Sometimes the most honest approach is also the simplest.

5. The Role of Space and Scale in Environmental Understanding

Adams’ masterful use of scale is perhaps best exemplified in his work “From the Missouri West” (1980), where he systematically explores the relationship between human development and the vast Western landscape. Unlike his contemporaries who often emphasized either the grandiosity of nature or the impact of human development, Adams found ways to show both simultaneously, creating complex visual statements about our place within the natural world.

Consider his photograph of a highway cutting through Wyoming grasslands. The road itself occupies only a small portion of the frame, while the surrounding prairie and sky dominate the composition. This deliberate choice in scale makes human intervention seem simultaneously significant (in its permanent alteration of the landscape) and insignificant (against the sheer vastness of the Western space). The tension between these two readings creates a nuanced commentary on human ambition and natural permanence.

Adams’ work in Oregon later in his career further developed this approach. His coastal photographs often show tiny human structures – houses, fences, roads – against the enormous backdrop of the Pacific Ocean, creating what he called “a geography of hope” where human presence exists in proportion to, rather than in domination of, the natural world.

Takeaway: Scale can be used as a powerful narrative tool, creating visual relationships that speak to larger environmental and philosophical concerns. Consider how the relative size of elements in your frame can convey meaning about their importance and relationship.

6. Time and Change: The Documentary Imperative

Adams’ long-term documentation of specific regions represents one of the most comprehensive visual records of environmental transformation in American photography. His work in Colorado spans from the 1960s through the 1980s, creating an invaluable chronicle of how rapid development transformed the Front Range landscape.

“Denver: A Photographic Survey of the Metropolitan Area” (1970-1974) exemplifies this approach. Adams systematically photographed the city’s expansion, returning to locations multiple times to document their transformation. One striking sequence shows a tract of prairie grassland transformed into a suburban development over just eighteen months. The series begins with untouched prairie, moves through stages of construction, and ends with completed homes and paved streets – a visual record of landscape transformation that would otherwise go unnoticed in its gradual progression.

This attention to time and change continues in his later work. “Turning Back” (2005) examines the logging industry’s impact on the Pacific Northwest over decades, creating a powerful document of environmental change that works through accumulation of evidence rather than dramatic individual images.

Takeaway: Consider how photographing changes over time can reveal patterns and transformations that might be invisible in single moments. Long-term documentation can create powerful statements about environmental change and human impact.

7. The Ethics of Representation in Environmental Photography

Adams’ approach to environmental photography is deeply rooted in ethical considerations about how to represent both nature and human intervention. Unlike many environmental photographers who seek out the most dramatic examples of destruction or the most pristine examples of wilderness, Adams consistently focuses on the more common, everyday landscapes where most people actually live.

This ethical stance is particularly evident in “Our Lives and Our Children” (1983), where he photographed communities near the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant. Rather than focusing on obvious environmental damage or protest movements, Adams photographed ordinary people going about their daily lives in the shadow of potential disaster. This approach created a more complex and humane document than simple environmental advocacy might have achieved.

As he wrote in “Beauty in Photography,” the photographer’s responsibility is “to record what is beautiful in the world and to resist being won over by what is not.” This seemingly simple statement underlies a sophisticated ethical framework that acknowledges both beauty and damage, hope and loss.

Takeaway: Develop a clear ethical framework for representing environmental issues. Consider how your choices in what to photograph and how to photograph it reflect deeper moral considerations about truth-telling and advocacy.

8. The Power of Sequence and Series

Adams’ books and exhibitions demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of how photographs work in sequence to build meaning. Unlike many photographers who rely on individual “strong” images, Adams often works in extended series where the cumulative effect of many photographs creates a more complex understanding than any single image could achieve.

“What We Bought: The New World” (1970-1974) exemplifies this approach. The book presents a systematic survey of Denver’s suburban landscape, moving from new housing developments to shopping centers, parking lots, and recreational spaces. No single image tells the whole story; instead, the accumulation of evidence creates a comprehensive portrait of how consumer culture was reshaping the American West.

This approach continues in later works like “Tree Line” (2009), where sequences of photographs showing the gradual transition from plains to mountains create a meditation on natural boundaries and ecological zones. The power comes not from individual dramatic images but from the patient accumulation of visual evidence.

Takeaway: Consider how images work together to build meaning. Sometimes a carefully constructed sequence of quieter images can be more effective than a single dramatic photograph.

9. The Human Presence in Absence

One of Adams’ most powerful techniques is his ability to convey human presence through its absence. This approach is particularly evident in “Prairie” (1978), where photographs of seemingly empty landscapes are marked by subtle signs of human intervention – fence lines, tire tracks, distant buildings. These traces become more powerful than direct representations of people would be, suggesting humanity’s pervasive influence on even apparently untouched spaces.

Consider his photograph of a prairie at dusk, where the only direct evidence of human presence is a single fence post. The image gains its power from what isn’t shown – the vast system of property division and land use that single post represents. As Adams wrote in “Why People Photograph,” “By implying people while showing them only rarely, we can suggest that everything we see is a product of human presence.”

This technique reaches its fullest expression in “Summer Nights, Walking” (1976-1982), where empty suburban streets and illuminated windows suggest human presence while never showing people directly. The effect is both ghostly and intimate, suggesting how human presence shapes space even in its physical absence.

Takeaway: Consider how absence can be as powerful as presence in photography. What isn’t shown can often speak more eloquently about human influence than direct representation.

10. Technical Precision as Moral Imperative

Adams’ technical approach to photography reflects his belief that clarity and precision are moral as well as aesthetic choices. Using primarily a medium-format camera and working almost exclusively in black and white, Adams develops his prints to maintain detail in both highlights and shadows, ensuring that every aspect of the scene is clearly visible.

This technical precision is particularly evident in “Los Angeles Spring” (1986), where his photographs of smog-filled valleys required exceptional control of tonal range to capture both the pollution’s effect on light and the landscape’s underlying structure. Adams has written that this attention to detail reflects a “responsibility to see clearly,” arguing that technical shortcuts amount to a form of dishonesty about the world we’ve created.

His choice to work in black and white is similarly purposeful. As he explained in “Beauty in Photography,” removing color allows viewers to focus on form and light, creating a slight abstraction that paradoxically makes the reality of what’s shown more apparent.

Takeaway: Technical choices are never neutral – they reflect and communicate values. Consider how your technical decisions support or undermine your larger purpose as a photographer.

11. Light as Environmental Witness

Throughout his career, Adams has used light not just as an aesthetic element but as a way to reveal environmental truth. His work in Los Angeles during the 1970s and 1980s shows how he adapted his technique to capture the particular quality of light in a polluted atmosphere, creating images that are both beautiful and disturbing.

In “California: Views by Robert Adams of the Los Angeles Basin 1978-1983,” he captured how smog affects the quality of sunlight, creating a kind of terrible beauty that speaks to environmental degradation. One remarkable image shows a housing development through a haze of pollution, the light simultaneously ghostly and revealing. Adams noted that “even in our damaged world, the light itself remains undiminished.”

This attention to light as environmental indicator continues in his later work in Oregon, where the quality of light through coastal fog and forest canopy reveals subtle ecological relationships

Takeaway: Light can be used not just for aesthetic effect but as a way to reveal environmental conditions and changes. Pay attention to how different qualities of light can communicate environmental realities.

12. Architecture as Environmental Index

Adams’ approach to photographing buildings differs significantly from traditional architectural photography. Rather than celebrating architectural design, he uses buildings as indicators of human values and environmental relationship. This is particularly evident in “denver: A Photographic Survey of the Metropolitan Area” (1970-1974), where his documentation of tract homes, strip malls, and office buildings reveals patterns of development and resource use.

His photograph of a new suburban church, for example, shows not just the building but its relationship to the surrounding landscape, parking lots, and infrastructure. The image becomes a commentary on how religious architecture, traditionally a culture’s highest architectural expression, has been transformed by car culture and suburban development.

In later work like “Commercial/Residential” (1998), Adams examined how architectural styles reflect changing attitudes toward the landscape, documenting how commercial architecture increasingly turns its back on the natural world.

Takeaway: Buildings can be read as documents of cultural values and environmental relationships. Consider how architectural photography can reveal more than just design choices.

13. The Role of Time in Environmental Photography

Adams’ understanding of photographic time goes beyond simple documentation. His work demonstrates how different temporal scales – geological time, human time, and photographic time – interact in environmental photography. This is particularly evident in his images of clear-cut forests in “Turning Back” (2005), where the instantaneous exposure captures a moment within a much longer process of environmental change.

In photographing logged areas, Adams shows both the immediate aftermath of cutting and signs of forest succession, creating images that compress different temporal scales into a single frame. His careful attention to light and atmospheric conditions adds another temporal layer, suggesting how momentary beauty exists even in damaged landscapes.

Takeaway: Consider how different scales of time can be suggested within a single photograph. Environmental photography often requires thinking about how to represent both immediate conditions and longer-term processes.

14. The Question of Hope

Throughout his career, Adams has grappled with how to maintain hope while documenting environmental destruction. This struggle is perhaps most evident in “Pine Valley” (2005), where his photographs of a small Oregon community suggest possibilities for sustainable human presence in the landscape.

Rather than focusing solely on environmental damage, Adams includes images of successful adaptation and coexistence. A photograph of a well-maintained small farm against a forest backdrop, for instance, suggests how human activity can complement rather than destroy natural systems. As he wrote, “Is there a reason to hope that we can live responsibly in the landscape? I believe there is, and that the reason is beauty.”

Takeaway: Consider how to balance documentation of environmental problems with examples of positive human-nature relationships. Hope can be as important as criticism in environmental photography.

15. The Legacy of Survey Photography

Adams’ work consciously builds on the tradition of 19th-century survey photography while adapting it to contemporary environmental concerns. Like his predecessors Timothy O’Sullivan and William Henry Jackson, Adams undertakes systematic documentation of Western landscapes. However, where they photographed an apparently untamed wilderness, Adams documents a landscape shaped by human activity.

His methodical approach in projects like “What We Bought” (1974) explicitly references survey photography’s documentary strategies while turning them toward contemporary subjects. This connection to historical practice gives his work additional depth and context, suggesting how photographic seeing itself has evolved alongside landscape change.

Takeaway: Understanding and building on historical photographic traditions can enrich contemporary practice. Consider how your work relates to and differs from historical precedents.

Conclusion

Robert Adams’ photography offers insights into both the practice of photography and our relationship with the natural world. His ability to find beauty in compromised landscapes while maintaining clear-eyed documentation of environmental change provides an essential model for contemporary environmental photography. Through careful observation, technical precision, and ethical awareness, his work demonstrates how photography can serve both as art and as a crucial record of environmental transformation.

His approach is a reminder that significant photography often emerges from sustained attention to familiar places rather than exotic locations or dramatic events. By focusing on the ordinary landscapes of the American West, Adams reveals extraordinary insights about our relationship with the environment and the consequences of our actions upon it.