Mary Ellen Mark‘s contribution to photography extends far beyond the remarkable images she created over her four-decade career. Her methodology represents a masterclass in the delicate balance between technical excellence and human connection, between artistic vision and ethical responsibility. This comprehensive analysis explores her approach to photography through the lens of her major works, teaching philosophy, and the evolution of her practice.

The Foundation: Patient Observation and Deep Immersion

Mary Ellen Mark’s approach to observation fundamentally challenged the rapid-fire methodology that dominates much of contemporary photography. Her work on Ward 81 at the Oregon State Hospital provides perhaps the clearest example of her immersive approach. Before taking a single photograph, Mark spent several weeks living alongside the women in the ward, sharing their daily routines, meals, and spaces. This wasn’t simply about gaining access or building trust – though it accomplished both – but about developing a deep understanding of the rhythms and realities of life in the ward.

“You don’t just walk in with a camera and expect to capture truth,” Mark often told her students. “You have to become part of the fabric of the place.” This philosophy was evident in her approach to Falkland Road, her groundbreaking work documenting Mumbai’s sex workers. For weeks, Mark would walk the street without a camera, enduring harassment and occasional violence. She described how locals would throw garbage at her, yet she returned day after day, establishing her presence not as a photographer, but as a persistent, respectful observer.

This patient observation extended to her technical preparation. While waiting and watching, Mark would study the light patterns in different locations throughout the day. She would note when and where interesting interactions occurred, mapping out the social geography of her subjects’ worlds. In her street photography workshops, she taught students to spend at least a day in a location without taking photos, just observing and taking notes.

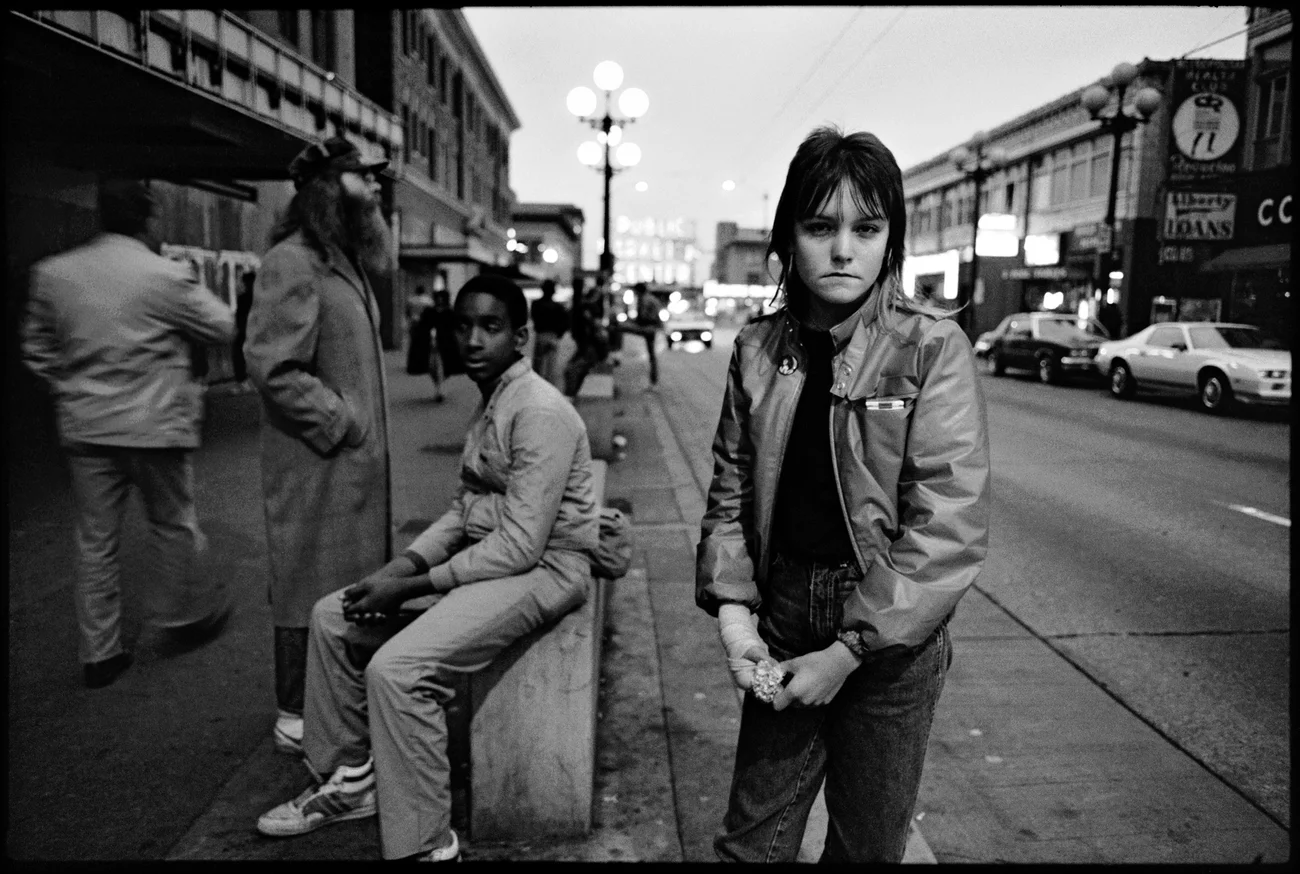

The depth of this observational approach became particularly evident in her long-term projects. With Tiny, the Seattle street kid she photographed for over 30 years, Mark’s initial patient observation evolved into a decades-long documentation of one life. She witnessed and recorded Tiny’s transformation from a 13-year-old sex worker to a mother of ten, maintaining contact even when not photographing. This long-term connection allowed Mark to capture moments of extraordinary intimacy and honesty that would have been impossible with a more superficial approach.

Key Takeaways:

- Immersion before photography: Lived with subjects, shared routines, understood daily life patterns

- Establishing presence: Visited locations repeatedly without camera, endured resistance, became familiar figure

- Technical observation: Studied light patterns, mapped interactions, documented location dynamics

- Long-term commitment: Maintained relationships over decades, documented life changes, built lasting trust

- Success through persistence: Endured initial hostility for deeper access and authentic moments

Technical Mastery: The Tools of Connection

Mark’s technical approach was intrinsically linked to her observational methodology. She was known for matching her choice of camera format to the specific demands of each project, but this selection went beyond mere technical considerations. Her use of different formats reflected a deep understanding of how camera choice affects the photographer-subject relationship.

When working on street photography projects, Mark predominantly used 35mm Leica cameras. The relatively small size and quiet operation of these cameras allowed her to work unobtrusively, maintaining the natural flow of street life. However, she approached even this potentially spontaneous format with careful preparation. “I would pre-focus at common distances,” she explained in workshops. “Five feet, eight feet, fifteen feet. I knew these distances by instinct and could adjust without looking through the viewfinder.”

For her more formal documentary work, particularly in projects like Indian Circus and her later portraits, Mark often chose medium format cameras. The shift to medium format wasn’t simply about image quality – it represented a different way of engaging with subjects. The slower pace required by these cameras matched her methodical approach to formal portraiture. When photographing circus performers in India, the deliberate process of working with a medium format camera helped create a sense of occasion that her subjects responded to.

Perhaps most distinctive was her use of the massive 20×24 Polaroid camera, particularly in projects like Twins and Prom. The camera’s size and complexity required subjects to become active participants in the photographic process. “With the 20×24, there’s no hiding what you’re doing,” Mark explained. “It becomes a collaboration between photographer and subject.” The immediate feedback provided by the Polaroid process also allowed subjects to participate in the image-making decisions, further breaking down the traditional photographer-subject power dynamic.

Key Takeaways:

- Camera choice dictated by project needs: Selected formats based on how they affected photographer-subject dynamics

- 35mm approach: Used Leica for street photography, pre-focused at set distances, maintained unobtrusive presence

- Medium format strategy: Employed for formal work, slower pace created sense of occasion, suited methodical portraiture

- Polaroid technique: 20×24 camera made photography collaborative, immediate feedback involved subjects in process

- Technical choices served relationships: Each format decision based on how it would impact connection with subjects

The Art of Human Connection

Mark’s approach to building relationships with subjects set a new standard in documentary photography. Unlike photographers who maintain deliberate distance from their subjects, or those who pursue quick intimacy for immediate results, Mark developed a methodology based on sustained, honest engagement. This approach is perhaps best illustrated through her work on Falkland Road, a project that initially seemed impossible due to the closed nature of Mumbai’s red-light district.

Mark spent months building relationships with the women of Falkland Road, beginning with Saroja, a madam who eventually became her entry point into the community. “The first time I walked into a brothel, everyone screamed and ran,” Mark recalled. “But I kept coming back. Not to photograph – just to be there.” This persistence, combined with genuine interest in her subjects’ lives, eventually led to such deep trust that when police raided the brothels, the women would hide Mark under their beds.

The depth of these relationships fundamentally affected the resulting photographs. In one striking image, a sex worker named Kamla is photographed through a partially opened curtain, a customer’s hand visible on her face. Such an intimate moment could never have been captured without the profound trust Mark had built. Yet Mark’s relationship-building went beyond accessing difficult moments – it was about understanding the full context of her subjects’ lives.

This approach carried through to her teaching. “If you’re just there to take pictures, people can sense that,” she would tell students. “You have to be genuinely interested in their lives, their stories, their world.” She encouraged photographers to spend time with subjects even when not photographing, to share meals, to listen to stories, to become part of their subjects’ world in a meaningful way.

Key Takeaways:

- Relationship priority: Built sustained connections before photography, rejected quick intimacy for deeper engagement

- Persistent presence: Maintained regular contact with subjects without photographing, focused on genuine interest

- Trust development: Earned unprecedented access through patience, leading to intimate documentary moments

- Context understanding: Prioritized knowing subjects’ full lives and stories over just capturing images

- Teaching philosophy: Emphasized genuine interest in subjects’ lives, encouraged meaningful engagement beyond photography

Project Development and Execution

Mark’s approach to developing and executing projects was methodical and comprehensive. Her work on “Ward 81” provides a master class in project development. Before beginning photography, she spent months researching the history of mental health treatment, studying previous photographic works on similar subjects, and developing relationships with hospital staff. She wrote detailed proposals outlining her intentions and methodology, establishing clear protocols for working with vulnerable subjects.

The execution phase of her projects was equally thorough. During “Streetwise,” her documentation of Seattle’s homeless youth, Mark developed a systematic approach to maintaining contact with her subjects despite their transient nature. She would regularly visit known gathering spots, maintain contact with social workers and outreach programs, and create networks among the youth themselves to help locate subjects.

Most notably, Mark kept extensive documentation of her projects. Her contact sheets were annotated with detailed notes about technical settings, subject information, and contextual details. These notes weren’t just for her own reference – they became teaching tools in her workshops, demonstrating how thoughtful documentation supports long-term project development.

Key Takeaways:

- Thorough research: Conducted extensive background study, reviewed similar works, developed deep subject understanding

- Clear methodology: Created detailed proposals and protocols, especially for vulnerable subjects

- Systematic tracking: Developed networks and systems to maintain contact with transient subjects

- Detailed documentation: Maintained comprehensive notes on technical settings and context

- Teaching integration: Used project documentation as educational tools in workshops

The Workshop Philosophy

Mark’s teaching methodology was as distinctive as her photography. In her workshops, she emphasized the importance of developing not just technical skills but a personal vision. She approached teaching with the same patience she applied to her own work, often spending hours with individual students discussing single images.

A typical Mark workshop began not with camera technique but with observation exercises. Students were required to spend their first day without cameras, simply observing and taking notes about their chosen location or subject. She would tell them, “Before you can photograph a place or person, you need to understand what draws you to them. What story are you trying to tell?”

Her critique sessions were legendary for their thoroughness. Rather than offering quick judgments, she would lead students through detailed analyses of their images, considering not just technical and compositional elements but the photographer’s relationship with the subject and the ethical implications of their approach. “A photograph isn’t just about what’s in the frame,” she would say. “It’s about the entire process that led to that moment.”

Key Takeaways:

- Personal vision focus: Emphasized developing unique photographic perspective beyond technical skills

- Observation first: Required students to spend initial day watching and noting, without cameras

- Story emphasis: Pushed students to understand their motivation and narrative goals

- Thorough critique: Conducted detailed image analysis considering technical, relationship, and ethical aspects

- Process importance: Taught that final image reflects entire journey of creating it

Technical Innovation in Service of Human Stories

While Mark is often celebrated for her humanitarian approach, her technical innovation was equally important to her success. She developed specific techniques for different situations, always in service of telling human stories more effectively. Her work with the 20×24 Polaroid camera on the “Twins” project exemplifies this approach.

The massive camera’s technical limitations – limited depth of field, slow operation, expensive materials – became creative advantages in Mark’s hands. She used the shallow focus to create intimate portraits where the subjects seem to float in space. The camera’s size and complexity created a theatrical atmosphere that helped subjects engage with the process. The cost of materials forced careful consideration of each shot, leading to more thoughtful, deliberate compositions.

Similarly, her approach to lighting evolved to serve her documentary needs. In the brothels of Falkland Road, she developed a technique using bounced flash that maintained the environment’s rich color while providing enough light for proper exposure. This technical solution arose from her respect for the reality of the place – she wanted to illuminate but not alter the natural atmosphere.

Key Takeaways:

- Technical adaptation: Turned equipment limitations into creative advantages, particularly with 20×24 Polaroid

- Deliberate constraints: Used camera limitations to create more thoughtful compositions and engagement

- Documentary authenticity: Developed lighting techniques that preserved natural environment

- Subject emphasis: Adapted technical approach to serve storytelling and human connection

- Innovation purpose: Used technical solutions to enhance, not alter, reality of subjects’ environments

The Ethical Framework: Photography with Purpose

Mark’s ethical framework was not a set of abstract principles but a living philosophy that evolved through practical application. Her work with vulnerable populations – psychiatric patients, street children, sex workers – required constantly balancing the photographer’s duty to document with the human obligation to protect. This framework became most evident in her work with Tiny from “Streetwise.”

When Mark first photographed Tiny in 1983, she was a 13-year-old sex worker. The ethical complications were immense: How do you document a child in crisis without exploiting their vulnerability? How do you maintain journalistic distance while fulfilling adult responsibilities to a minor in danger? Mark’s solution was to develop a long-term relationship that transcended the typical photographer-subject dynamic. She maintained contact with Tiny for over three decades, documenting her life while also becoming a consistent adult presence.

“Photography isn’t just about taking pictures,” Mark would tell her students. “It’s about taking responsibility.” This responsibility extended to how images were used and presented. She was meticulous about context, insisting on accurate captions and fighting against sensationalistic presentations of her work. When photographing in Ward 81, she showed all images to the hospital staff and patients before publication, not seeking permission but ensuring dignity was maintained.

Mark’s approach to informed consent went beyond simple release forms. She developed a practice of ongoing consent, regularly checking in with subjects about their comfort with the process and their wishes regarding the use of their images. This was particularly important in her work with children and vulnerable adults. “Consent isn’t a one-time thing,” she explained. “It’s a continuous dialogue.”

Key Takeaways:

- Living ethics: Developed practical ethical framework through work with vulnerable populations, not abstract rules

- Balanced documentation: Navigated duty to document while protecting subjects, especially with vulnerable people

- Long-term responsibility: Maintained sustained relationships beyond photography, becoming consistent presence in subjects’ lives

- Context control: Insisted on accurate captions and appropriate presentation of images, avoiding sensationalism

- Ongoing consent: Practiced continuous dialogue about image use and subject comfort, beyond initial permissions

Street Photography: The Art of Unobtrusive Observation

Mark’s approach to street photography differed significantly from many of her contemporaries. While others might emphasize the decisive moment or graphic composition, Mark focused on finding moments of human connection even in anonymous street scenes. Her technique was built on careful preparation and patient waiting rather than reactive shooting.

When working on the streets of Bombay (now Mumbai), Mark would often position herself in one spot for hours, waiting for the right combination of elements to come together. She taught students to “build” their street photographs, starting with a strong background or interesting light pattern, then waiting for human subjects to enter the frame in meaningful ways.

Her technical approach to street work was equally methodical. She typically used a 35mm Leica with a 35mm lens, pre-focused at specific distances. “You should know your camera so well that it becomes invisible,” she would say. “All your attention should be on what’s happening in front of you.” She advocated for minimal equipment – usually just one camera and one lens – to maintain mobility and avoid drawing attention.

Key Takeaways:

- Human connection: Prioritized emotional resonance over decisive moments in street photography

- Methodical preparation: Built photos carefully with strong backgrounds, waited for elements to align

- Technical simplicity: Used minimal equipment (35mm Leica, 35mm lens), mastered pre-focusing

- Patient positioning: Waited in chosen spots for extended periods for right elements

- Complete focus: Emphasized knowing equipment so thoroughly it becomes invisible to concentrate on scene

Portrait Work: Beyond the Surface

Mark’s portrait methodology represented a unique fusion of formal technique and psychological insight. Whether working with celebrities on film sets or with circus performers in India, her approach centered on revealing authentic moments within formal constraints. This was particularly evident in her work with the 20×24 Polaroid camera.

The technical limitations of the massive Polaroid camera – its immobility, expensive materials, and slow operation – forced a more deliberate approach to portraiture. Mark would spend considerable time setting up each shot, but this technical preparation served a deeper purpose. “The time it takes to set up creates a space for real interaction,” she explained. “People relax into themselves.”

Her portrait sessions often began with conversation rather than photography. With actors and celebrities, she would spend time observing them on set before beginning to shoot. This allowed her to see beyond their public personas and capture more genuine moments. Her portraits of Marlon Brando on the set of “Apocalypse Now” demonstrate this approach – she waited until he was comfortable enough to play with insects, capturing a playful side of the notoriously difficult actor.

Key Takeaways:

- Technical/psychological blend: Combined formal technique with deep psychological understanding

- Deliberate constraints: Used technical limitations of equipment to create space for authentic interaction

- Conversation first: Started sessions with observation and dialogue before photography

- Patient authenticity: Waited for subjects to reveal genuine selves beyond public personas

- Setup purpose: Used technical preparation time to allow subjects to become comfortable

Documentary Projects: The Long View

Mark’s approach to long-form documentary work was characterized by sustained engagement and methodical development. Her projects often spanned years or decades, allowing her to document not just moments but transformations. This approach is perhaps best exemplified in her work with the circus communities in India.

Over multiple visits spanning many years, Mark documented not just the performances but the entire ecosystem of Indian circus life. She photographed training sessions, family moments, and the daily routines that supported the spectacular performances. This long-term engagement allowed her to capture both the magic and the mundane reality of circus life.

Her documentary methodology emphasized comprehensive coverage while maintaining artistic vision. She would create detailed shot lists but remain open to unexpected moments. “You need structure to find freedom,” she would tell students. “Know what you’re looking for, but be ready for what you find.”

Key Takeaways:

- Sustained engagement: Documented transformations over years rather than moments

- Comprehensive coverage: Captured entire ecosystems beyond main events, including daily routines

- Structured flexibility: Created detailed shot lists while remaining open to unexpected moments

- Extended timeline: Allowed projects to develop over years or decades

- Balanced approach: Combined systematic planning with adaptability to opportunities

The Legacy: Influencing Contemporary Practice

Mary Ellen Mark’s influence on contemporary photography extends beyond her images to her methodology and ethical framework. Her approach to long-term projects and subject relationships has become a model for documentary photographers worldwide. Her insistence on technical excellence in service of human stories continues to influence photographic education.

Perhaps most importantly, her work demonstrates that maintaining high ethical standards and achieving artistic excellence are not mutually exclusive goals. Her career proves that patience, respect, and genuine human connection can lead to more powerful images than aggressive or exploitative approaches.

Conclusion: The Integration of Art and Ethics

Mary Ellen Mark’s comprehensive approach to photography demonstrates that technical mastery, artistic vision, and ethical practice are inseparable elements of great documentary work. Her methodology shows that taking time – with subjects, with technique, with project development – leads to deeper, more meaningful images.

For contemporary photographers, Mark’s legacy offers a blueprint for ethical and effective practice. Her work reminds us that photography at its best is not just about capturing images but about understanding and honoring human experience. In an age of instant imagery and viral content, her methodical, respectful approach remains more relevant than ever.

The lessons she leaves behind – about patience, preparation, ethical responsibility, and human connection – continue to influence new generations of photographers. Her work demonstrates that the most powerful images come not from technical skill alone, but from the integration of technique, vision, and profound respect for human dignity.

Essential Principles of Mark’s Approach:

- Take time to understand your subject before beginning to photograph

- Develop genuine relationships based on mutual respect

- Master technique so thoroughly it becomes invisible

- Maintain ethical standards regardless of circumstance

- Document comprehensively while maintaining artistic vision

- Return to subjects and stories over time

- Use technical choices to support human connection

- Preserve dignity while revealing truth

- Build trust through consistent ethical practice

- Remember that great photographs serve both art and humanity