Beyond Moral Absolutes: A Postmodern Defense of Street Photography Against Sontag’s Moralism

Susan Sontag’s On Photography (1977) casts a long shadow over the medium, framing the camera as an instrument of voyeurism, detachment, and aestheticized suffering. She warns of its dehumanizing potential—how it reduces subjects to objects, transforms pain into spectacle, and numbs viewers into passive consumers of misery.

When I first encountered Sontag as a graduate student, her work felt unavoidable, a theoretical North Star guiding my early attempts to grapple with the ethics of public photography. But with each rereading, her moralism grew harder to stomach. What she presented as ethical imperatives began to feel less like a dialogue and more like commandments—delivered, no less, from the remove of a Manhattan apartment, an ivory tower in all but name.

Revisiting her arguments through postmodern and post-structuralist lenses, I watched her certainties dissolve. These frameworks reveal her rigid moralism as a modernist relic, ill-equipped to account for photography’s lived complexities. Rather than a medium doomed by its exploitative gaze, street photography emerges as a contested space—where meaning multiplies, authority destabilizes, and representation becomes an ongoing negotiation rather than an inherent ethical failure.

Postmodernism resists definition by its very nature—it critiques grand narratives, destabilizes fixed meanings, and thrives on contradiction.

To pin it down is to violate its core principle: that truth is fragmented, provisional, and context-dependent. Even calling it a “movement” feels too coherent, as postmodern thought rejects such tidy categorizations.

Yet this elusiveness is its definition—a philosophy built on skepticism toward philosophy itself, where the act of questioning becomes the only constant. The more we try to contain it, the more it slips away, proving its own argument about the instability of knowledge.

And it is here, in photography’s unstable margins, that we find its radical potential. Not in the false purity Sontag demanded, but in the messy democracy of competing truths. The camera, when wielded with self-awareness, ceases to be a tool of objectification and instead becomes a participant in meaning’s endless reconstruction—precisely because it acknowledges its complicities rather than denying them through moral posturing.

1. The Death of the Author and the Birth of the Viewer’s Agency

Sontag’s moral framework hinges on a fundamental assumption: that the photographer’s intent dictates a photograph’s ethical weight. For her, the act of framing is inherently authoritarian—a violent extraction of agency from the subject. But Roland Barthes’ Death of the Author (1967) unravels this premise. Meaning, he argues, is unmoored from creator intent the moment an image enters the world. The viewer, not the photographer, becomes the site of interpretation.

Take Garry Winogrand’s Central Park Zoo (1967), in which a Black man and a white woman each cradle a chimpanzee. Winogrand, famously indifferent to explicit political messaging, likely saw this as mere visual play—a cheeky juxtaposition of species and race. Yet contemporary audiences dissect it through postcolonial and racial justice lenses, revealing layers of meaning he may never have intended. The chimps, historically used to dehumanize Black subjects, now refract the image’s implied hierarchies; the racialized pairing echoes America’s unresolved tensions. The photograph, once inert, becomes a contested text.

Postmodern Defense:

Street photographs are not static moral statements but evolving texts. Their ethical weight lies in the viewer’s interrogation, not the photographer’s purity of intent.

As Barthes wrote,

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.”

2. Deconstructing Binaries: Voyeurism vs. Collaboration

Sontag’s critique hinges on a rigid binary: the photographer as voyeur, the subject as passive victim. But Jacques Derrida—the Algerian-French philosopher who revolutionized 20th-century thought by exposing the instability of language and meaning—demolishes such oppositions as false constructs. His method, deconstruction, reveals how Western philosophy relies on hierarchical pairs (speech/writing, presence/absence, self/other) where one term dominates artificially. For Derrida, these binaries are not natural but enforced—and photography, with its illusion of objective capture, is fertile ground for their unraveling.

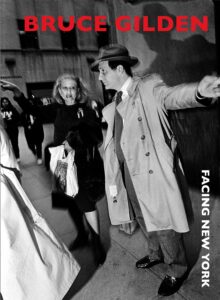

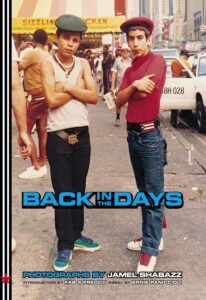

This is why street photography’s ethical debate demands deconstruction: the medium thrives in liminal spaces between observation and participation, extraction and exchange. Jamel Shabazz’s Back in the Days (2001) exemplifies this collapse. His portraits of Black and Latino youth in 1980s Brooklyn—posed in Kangol hats and Adidas sneakers, their bodies angled with deliberate cool—are not candid “thefts” but acts of collaboration. A former corrections officer, Shabazz worked with his subjects, not on them, crafting images of defiance and dignity. Here, the gaze is not imposed but reclaimed, a tool of self-representation that Derrida might call a supplement: an addition that exposes the original (the racist, voyeuristic gaze) as incomplete.

Judith Butler’s notion of identity as performance (Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) extends this logic. Shabazz’s subjects are not “caught” by the camera; they perform for it, their stylized gestures—the tilt of a brim, the fold of arms—asserting agency within the frame. The photograph becomes a stage where identity is iterated, not a trap where it’s fixed. Sontag’s moralism, rooted in modernist certainties, cannot accommodate this fluidity.

Derrida’s genius was showing how meaning slips through the cracks of imposed structures. In street photography, this means acknowledging both the camera’s coercive potential and its capacity for reciprocity—precisely the paradox Sontag’s framework cannot hold.

3. Hyperreality and the City as Simulacrum

Sontag laments photography’s detachment from reality, accusing it of substituting images for lived experience. But Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981) argues reality itself is already a simulacrum—a copy without an original. Street photographers don’t distort reality; they mirror its constructedness and expose its fragility. As Baudrillard wrote, “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth—it is truth that hides the fact that there is none.”

Sontag condemns photography as a retreat from reality—a medium that substitutes images for lived experience. But Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981) shatters this premise: what if reality itself is already a simulacrum, a copy without an original? In the postmodern metropolis, where urban life is mediated by advertising, surveillance, and performance, street photographers don’t distort reality—they reveal its inherent constructedness.

Baudrillard’s hyperreality finds its purest expression in the work of photographers like Philip-Lorca diCorcia, whose Heads series (2001) captured strangers in Times Square with hidden strobe lights. These images—staged yet spontaneous, theatrical yet documentary—expose the city as a space where authenticity and artifice collapse. The subjects’ unawareness of being photographed doesn’t render them “authentic”; rather, it underscores how urban existence is always already performative. As Baudrillard declared: “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth—it is truth that hides the fact that there is none.”

Sontag’s lament assumes a stable reality waiting to be faithfully represented. But street photography’s power lies in its refusal of this nostalgia. When we view Jeff Wall’s meticulously constructed Mimic (1982)—a seemingly candid racial confrontation staged to echo a witnessed moment—we confront photography’s deepest provocation: that all representation is negotiation, and the “real” is just another pose waiting to be framed.

4. Power/Knowledge and the Democratization of Gaze

Sontag’s critique relies on a simplistic power dynamic: photographer as oppressor, subject as victim. Michel Foucault’s radical rethinking of power—developed across works like Discipline and Punish (1975) and The History of Sexuality (1976)—shatters this binary. For Foucault, power isn’t a top-down force but a capillary network that circulates through every social interaction. It produces knowledge, shapes identities, and even generates resistance. This framework transforms how we understand street photography’s ethical dimensions.

Foucault’s Key Contributions:

- Power is productive, not just repressive: It doesn’t merely suppress; it creates behaviors, norms, and ways of being seen.

- The panoptic principle: Modern society disciplines bodies through the threat of surveillance—a concept street photography literalizes.

- Power/knowledge regimes: What counts as “truth” is determined by systems of control (e.g., documentary photography’s claim to objectivity).

Bruce Gilden’s work exemplifies this complexity. His invasive flash doesn’t just capture subjects—it stages a micro-power struggle. When his lens triggers a recoil, we witness Foucault’s docile bodies reacting to sudden surveillance. Yet these very reactions—the grimace, the raised hand, the defiant stare—are acts of resistance within the power/knowledge matrix. Gilden’s subject isn’t powerless; they’re negotiating visibility on their own terms. Gilden’s work also exposes the transactional nature of public space.

The deeper irony:

Gilden’s aggression mirrors Foucault’s insight about power’s theatricality. By exaggerating photographic domination, he exposes the implicit contract of public space: we’re all simultaneously surveillers and surveilled. Sontag’s moralism collapses under this weight—her framework can’t account for how power, like light, refracts through every gaze exchanged on the street.

5. Embracing Fragmentation: Lyotard’s Anti-Metanarratives

Sontag demands photography serve a coherent moral purpose—to inform, to protest, to humanize. She envisions the camera as an instrument of clarity, where every image should advance a singular ethical imperative. Yet Jean-François Lyotard’s postmodernism reminds us this demand itself constitutes a grand narrative—one that crumbles under the weight of lived complexity.

Street photography’s greatest works don’t resolve moral dilemmas; they sustain them. Consider Garry Winogrand’s chaotic sidewalks, where intention and accident collide, or Vivian Maier’s stolen glances that hover between empathy and intrusion. These images don’t document truth—they multiply it, creating spaces where multiple, often contradictory realities coexist.

The ethical power of street photography lies precisely in what Sontag fears: its refusal to reduce human experience to simple moral equations. Where she sees dangerous ambiguity, postmodernism recognizes the necessary messiness of representation. A photograph’s meaning isn’t fixed by the photographer’s intent, but emerges in the unstable space between subject, maker, and viewer—a continuous negotiation that resists final judgment.

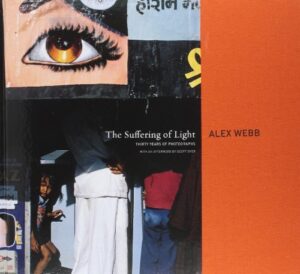

Alex Webb’s The Suffering of Light (2011)—with its layered subframes, borders, and shadows—refuses to reduce chaos to a single “truth.” Webb’s images resist didacticism, offering instead a visual echo of Lyotard’s “incredulity toward metanarratives.”

Postmodern Defense:

Street photography’s value lies in its refusal to simplify. It mirrors life’s irreducible complexity.

6. Performativity and the Drama of the Street

Sontag’s critique rests on an assumption: that street photography reduces subjects to passive victims of the gaze. But Judith Butler’s theory of performativity—articulated in (Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990)—reveals identity not as something we are, but something we do through repeated, citational acts. Street photography, then, doesn’t “steal” souls; it documents the theater of public life, where selves are performed and reinscribed with every gesture, glance, and pose.

Helen Levitt’s Two Children Dancing (1940) captures this perfectly. The boy and girl mid-twirl on a New York sidewalk aren’t merely “caught” in motion—they’re performing childhood itself, their spontaneous yet ritualized movements echoing the cultural scripts of play. Levitt’s lens doesn’t exploit; it bears witness to the joy of self-creation in the urban everyday.

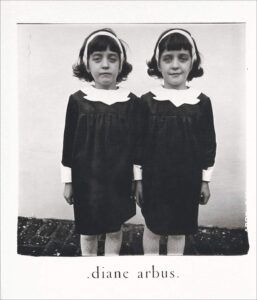

Diane Arbus’s Identical Twins, Roselle, NJ (1966) takes this further. The twins’ mirrored stances aren’t accidental; they’re a deliberate staging of sameness, a performance so precise it unsettles. Arbus doesn’t expose their “true” selves—she reveals identity as a construct, a series of gestures that cite normality until it cracks under scrutiny. The power of the image lies in its refusal to resolve: Are the twins conforming to or mocking the idea of uniformity?

Butler’s framework forces us to rethink Sontag’s moralism. If identity is performative, then the street photographer isn’t a thief but an archivist of the communal stage—where subjects, knowingly or not, rehearse and revise the scripts of selfhood. The ethical question shifts: not whether photography “takes” agency, but how it reveals agency’s relentless, collaborative production.

7. Différance and the Ethics of Unfixed Meaning

Susan Sontag’s moral framework demands that photography stabilize meaning—that context, framing, and authorial intent should anchor an image’s ethical weight. For her, ambiguity risks complicity; clarity is a moral imperative. But Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance—a cornerstone of deconstruction—shatters this illusion, revealing meaning as perpetually deferred, oscillating between presence and absence, said and unsaid.

Derrida’s Radical Intervention:

Derrida coined différance (spelled with an a to signify its dual function) to describe how language—and by extension, all representation—never fully “arrives” at meaning. The term puns on the French différer (“to defer” and “to differ”), capturing two key ideas:

- Differing: Meaning arises from contrast (e.g., “light” is defined against “dark”).

- Deferring: Meaning is postponed through an endless chain of signifiers (a word points to other words, never to a fixed referent).

For Derrida, this instability isn’t a flaw but a condition of communication. There’s no “transcendental signified”—no ultimate truth outside the play of language.

Street Photography as Deconstruction in Action:

Street photography, in its most potent form, doesn’t just tolerate this instability—it embodies it. Where Sontag sees irresponsibility in ambiguity, street photography finds ethical rigor in acknowledging the limits of representation.

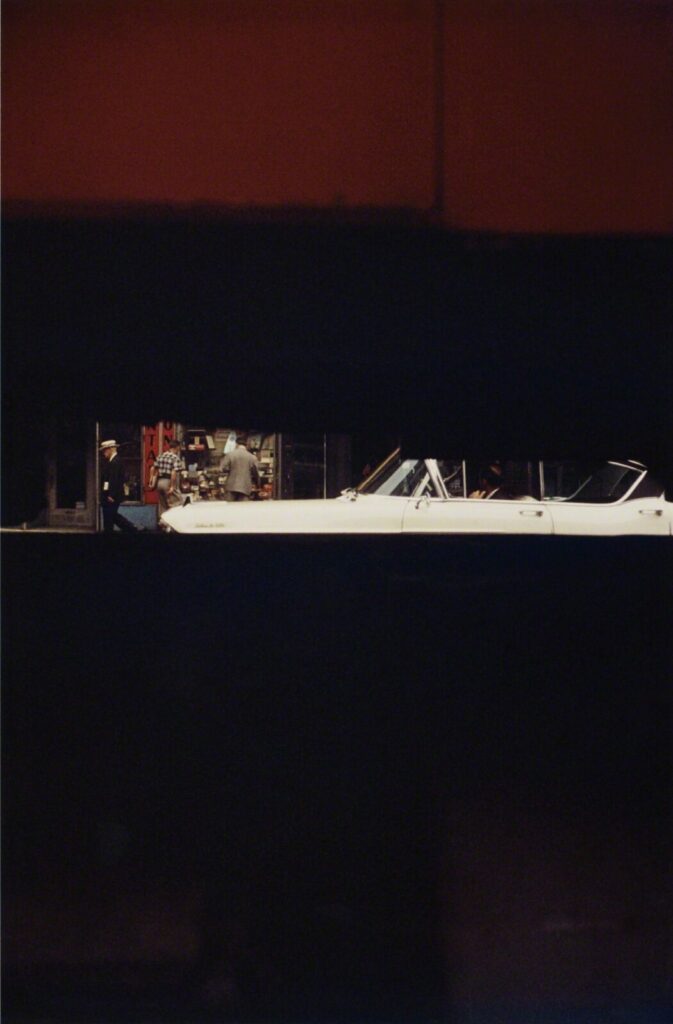

Consider Saul Leiter’s Through Boards (1957), where a figure is fragmented by obstructions. The image doesn’t hide its partiality; it insists on it. Like différance, Leiter’s work suggests meaning through what’s obscured, inviting the viewer to confront their own projections.

Ethical Implications:

- Against Authoritarian Framing: Sontag’s demand for narrative control assumes the photographer can (or should) dictate meaning. Derrida shows this is impossible—and that the attempt risks silencing the Other.

- The Viewer’s Responsibility: If meaning is co-created, the ethical burden shifts from “Did the photographer exploit?” to “How do I participate in this image’s politics?”

- Humility Over Certainty: As Derrida wrote, “There is nothing outside the text”—no singular truth, only interpretations in flux. Street photography’s power lies in its refusal to simplify.

Why This Matters Now:

In an era of deepfakes and algorithmic curation, Derrida’s insight is urgent: all images are unstable texts.

Street photography’s ethics begin where Sontag’s end—not in moral certainty, but in the sustained encounter with the unknowable.

8. Reclaiming the Marginalized Gaze

Sontag’s moral framework, while rigorous, emerges from a distinctly Western anxiety—one that universalizes the photographer’s power while ignoring how marginalized practitioners have reclaimed the medium. Postmodernism, with its insistence on situated knowledge and fractured perspectives, dismantles this hegemony. Street photography, when practiced by those historically excluded from its canon, doesn’t just document—it disrupts.

Decolonizing the Frame: Raghubir Singh’s Radical Color

Raghubir Singh’s River of Colour (1998) and The Grand Trunk Road (1995) explode the colonial imaginary. Where Western photographers like Cartier-Bresson imposed monochrome austerity on India, Singh’s saturated hues—saffron dust, turquoise trucks—assert a visual language that refuses exoticism. His insider perspective doesn’t “capture” India; it inhabits its chaos and vitality, subverting what Derrida might call the “metaphysics of presence” in ethnographic photography.

Collaborative Resistance: LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Flint as Family

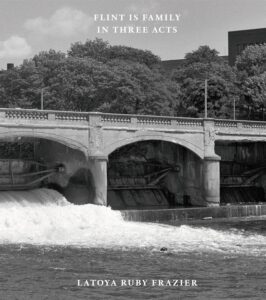

Likewise, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Flint is Family (2016) takes this further. Her portraits of water crisis survivors aren’t extracted “evidence” but co-authored testimonies. By embedding herself in the community (even sharing royalties with subjects), she rejects the colonial logic Sontag critiques—not by abandoning the camera, but by transforming its social contract. The work echoes bell hooks’ call for an oppositional gaze: the marginalized looking back, defining their own image.

The Postmodern Defense:

Street photography’s ethics aren’t inherent to the medium but to its use. Like a language, it can oppress or liberate:

- Amplifying Power: The colonial photographer extracts, freezes, and exoticizes.

- Disrupting Power: The insider collaborates, contextualizes, and implicates.

As Homi Bhabha notes, hybridity—the blurring of “self” and “other”—undoes colonial binaries. Singh’s India and Frazier’s Flint aren’t “othered” but centered, their complexity preserved. Sontag’s universalism collapses here; the camera’s morality depends not on its nature, but on whose hands hold it, and who it serves.

Why This Matters:

In an era of smartphone documentation and algorithmic bias, these practices model an alternative: photography as solidarity, not surveillance. The marginalized gaze, once excluded, now demands its right to opacity—to be seen on its own terms.

Street photography isn’t inherently immoral—it’s a tool that can amplify or disrupt power, depending on who wields it.

9. The Street as Archive: Memory and Forgetting

Sontag’s anxiety—that photography replaces lived experience—presumes a binary between memory and its representation. But postmodernism reveals the street as a palimpsest, where images accrue meaning through accumulation and erasure. The photograph doesn’t displace memory; it becomes a site of contested remembrance, holding what dominant histories exclude.

Daido Moriyama’s Stray Dog (1971): Trauma as Grain

Moriyama’s infamous snapshot—a grained, high-contrast stray dog mid-pant—transcends documentation. The image’s technical “flaws” (blur, glare, crushed shadows) mirror Japan’s postwar psyche: fractured, unresolved, resisting the neat narratives of economic revival. Like Walter Benjamin’s dialectical image, it arrests time to expose contradictions—here, between modernity’s shine and its shadows. This isn’t a record of a dog but a symptom of collective disquiet.

The Unfinished Archive

Street photography’s power lies in its fragments:

- Vivian Maier’s undeveloped rolls, discovered posthumously, challenge the myth of artistic intentionality.

- Fernell Franco’s Interiores (1980s)—ghostly images of Cali’s marginalized—preserve what gentrification erased.

These works don’t “replace” experience; they counter amnesia. As Derrida argued in Archive Fever, preservation is always also suppression—what’s included excludes. Street photographers, often working at society’s edges, archive the unarchivable: the glances, scars, and silences that resist institutional memory.

Why Sontag Misses the Point

Her lament assumes a pure, unmediated past. But memory is mediation. The street photograph’s blur, its cropping, its very instability—like Moriyama’s dog, forever snarling in grain—remind us: history isn’t a story told, but a wound that is still raw.

Postmodern Defense:

The street doesn’t need to be “faithful.” It needs to be faithless to official narratives—to honor, in its incompleteness, what totalities erase.

Takeaway:

Street photography preserves the unresolved, the incomplete—the traces of history that official narratives erase.

10. Toward a Postmodern Ethics: Responsibility Without Certainty

Postmodernism doesn’t absolve street photography of ethical scrutiny—it redefines Postmodernism doesn’t let street photography off the hook—it replaces Sontag’s rigid moralism with something more demanding: an ethics of perpetual negotiation. Her framework, rooted in modernist absolutes, crumbles when confronted with three irreducible truths:

- The Viewer as Co-Author

Meaning isn’t fixed by the photographer but forged in the act of looking. When we encounter Diane Arbus’s Identical Twins (1967), we don’t discover a “truth”—we confront our own unsettled reactions to their performative sameness. The image’s power lies in its refusal to resolve. - Subjects as Agents

From Jamel Shabazz’s collaborative portraits to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s embedded documentation, street photography reveals identity as enacted, not extracted. The subject who poses, scowls, or smiles for the lens isn’t passive—they’re negotiating visibility on their own terms. - The Camera as X-Ray

Far from obscuring power, street photography exposes its fractures. Bruce Gilden’s flash doesn’t just dominate; it theatricalizes domination, forcing viewers to reckon with their own voyeurism. The medium’s honesty lies in admitting its complicities.

Conclusion: The Ethics of Unknowing

Street photography doesn’t “steal” reality—it interrogates the very idea of a singular reality. As Daido Moriyama insisted, “To take a photograph is to confront the fragments of reality we cannot grasp.” In a postmodern world, this confrontation—messy, self-implicating, and relentlessly questioning—isn’t just ethical. It’s necessary.

Final Defense

Sontag’s moralism relies on a myth: that photography ever was, or could be, pure. Street photography’s radical potential lies in its refusal of this illusion. By embracing chaos, multiplicity, and subjectivity, it doesn’t transcend ethics—it embodies the postmodern condition. The question isn’t whether we represent the world, but how—and who gets to decide.

Further Reading:

- Barthes, Camera Lucida (on the punctum’s disruptive power)

- bell hooks, In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life (on reclaiming the gaze)

- Jeff Wall, Marks of Indifference (on photography as “near documentary”)

- Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (ethics as ongoing negotiation)

- Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (why “reality” was always a myth)